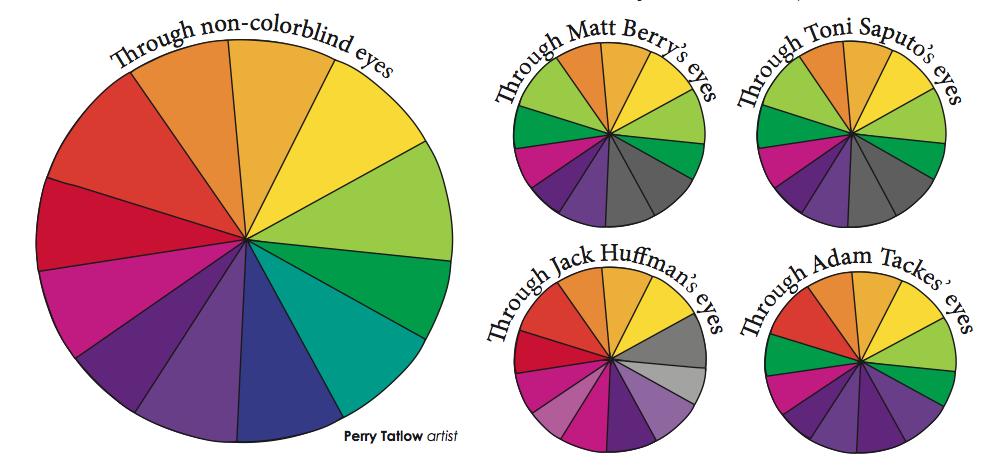

When Jack Huffman, sophomore, sits at a stoplight, he waits for the light to change to grey, not green. For Matt Berry, senior, being color blind will directly impact his future.

“I knew [I was color blind] when I was 3, and my family and I were at Build-A-Bear. I got a bear that at the time looked like a purple bear,” Matt Berry, senior, said. “Being 3 years old, I named it purple, but really it was navy blue. My parents were like, ‘You’ve got the wrong colors.’”

Berry and Huffman both took an Ishihara Test to test for the blindness. The assessment is different sizes of dots of one color in the shape of a circle, where the dots form a number of a different color. Those who are color blind may not see the number.

“We used to play a lot of ‘I Spy’ when I was little and no one would ever be able to figure out what I was looking at because I said it was the wrong color,” Huffman said. “You’ll look at one [color] and think it’s the other. It’s just weird. Green and grey are sometimes kind of confusing, purple and pink [are also confusing] and red, green and brown look alike.”

According to Color Vision Testing, the science behind color blindness is people need photoreceptors in the eyes to see. There are two types: rods and cones. Both are on the retina at the back of the eye and pass information to the brain. The rods are to see at night, but cannot perceive color while the cones have a light sensitive pigment to distinguish between colors during the day. Color blind people have a defect in the cones, which is why the colors are distorted, making the person color blind.

“Color blindness is a bad word for it. [I think its more like] color deficiency because if there are two colors right next to each other, like blue and purple, I’ll be able to tell the difference. It’s [harder to tell the difference when the colors are] far away,” Berry said. “Usually, I can tell the difference, but it gets a little frustrating.”

For Toni Saputo, senior, red looks like green and blue looks like grey. The confusion is more apparent in fabrics than anything else, which can make shopping and matching clothing difficult.

“Sometimes my mom will have to match my clothes,” Saputo said. “And I typically don’t wear red [because I do not like the way it looks].”

According to Colblindor, a website of statistics about color blindness, about 8 percent of all males and only 0.5 percent of all females suffer from it. Color blindness is found in the X chromosome. Males only have one X chromosome, whereas females have two. In females, if one X chromosome has color blindness, the stronger chromosome takes over.

“I was in [Sean] McCarthy’s class and everyone was saying he had [on] a bloutfit, and I was like ‘He is not wearing all blue because I thought his shirt was grey and his pants were Khaki’s,” Saputo said.

The way Adam Tackes, freshman, sees, red, green, brown, purple and blue all look alike. Particularly, blue and purple look like the same color and different shades of red look like green.

“I was in a 3-on-3 hockey league and my team color was red and we were playing a green team, and I couldn’t tell everybody apart, so I [had] to look at the helmets since they had black helmets and we had red helmets,” Tackes said.

Tackes and the others say they have learned to adapt to being color blind. Berry has not let that stop him from pursuing what he wants to do after high school.

“[Being color blind] affects what I do after school for the Army. You have to take an eye test. Because I failed the color blind test, I would have been excluded from the Navy or the Air Force,” Berry said. “I passed the red-green test for the Army, and that is the one that really matters.”