Ashya Lee reads at Kaldi’s as the last weeks of her summer dwindle away. “This summer has been fun. I didn’t have a lot of free time with school and work, but it was relaxing to get out of the classroom,” Lee said.

From teacher to student and back again

August 30, 2017

Colleen Curran, Special School District (SSD) teacher, attempts to compile her laptop, school supplies and homework on her way out of her front door. She steps out into the hot summer night and walks to her car. She lets out a sigh of relief, only in her car she can find quiet. She shifts into reverse and makes her way to Fontbonne University in Clayton.

Ten miles away, Laura Mortimer, SSD teacher, puts her 10-year-old son and newborn child to bed. Exhausted and coated in a thick layer of baby powder, she sits down on her couch and opens her laptop. She logs into Webster University’s website to participate in a discussion for homework.

Across St. Louis County Ashya Lee, SSD teacher, tells her daughter, 9-year-old Orie, that she cannot play with her. She watches as her daughter leaves her living room with her head down. Lee looks back at her but knows she needs to finish her homework.

All three teachers work with children who have behavioral and intellectual disabilities at Riverview Gardens. Side-by-side they enter the classroom everyday, collaborating with each other. However, once they all leave their classrooms as teachers they enter another classroom as students.

“I’m taking classes online to get my masters degree in special education,” Mortimer said. “After you’re done with school for the first time your body and brain think you’re done. Especially after being a teacher, it’s hard to go back to school and be a student again.”

Similar to Mortimer, Lee finds being a student again has some unintended side effects. After finishing the day at her part-time summer job, Lee turns her phone on airplane mode for days at a time to study. It’s the peak of finals week for her summer courses.

“I’m a social butterfly,” Lee said. “It’s hard for me [to not have time to socialize]. At the end of the day I just want to kick back and talk on my phone. I just don’t have the time. It seems like 24 hours just isn’t enough.”

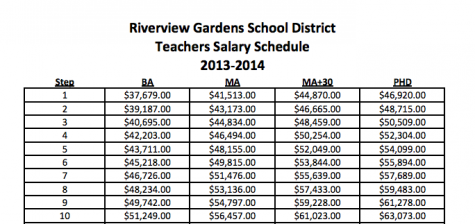

Along with the social and emotional effects of going back to school there is a financial aspect. According to Fontbonne University, an average cost per credit hour ranges from $442-$728. According to the Riverview Gardens School District (RGSD), a teacher with a Bachelor’s Degree can expect a salary $37,679 in RGSD.

Staff salaries of RGSD teachers according to year and and degree

“Making ends meet with bills, feeding and clothing my kids and going out every once in awhile with school costs can be overwhelming,” Curran said. “Even with financial aid and loans I’m still in $20,000 of debt. It’s really stressful.”

Between the financial, emotional and social strains of going back to school as an adult, these three teachers have put their money, time and effort into the endeavor. They had hoped that they would benefit from the experience, and all three are content with the results.

“One of the greatest things [about going back to college] is the online discussions,” Mortimer said. “I can connect with teachers from all over the country. We can share strategies and different teaching styles. I definitely apply the knowledge I’ve gained in my classroom.”

Mortimer acknowledged the benefits to her classroom and the kids who she teaches in going to college. However, Lee recognizes another benefit, touching on the potential pay raise that she could receive in being awarded her masters degree.

“There is a money part to it,” Lee said. “At the end of the day I want to be better at what I do and help the kids, but at the same time I need to provide for my own child. I think I deserve more. If I can make more money getting my masters [degree] I’m going to jump on that opportunity.”

According to Futuresource, the educational landscape and how the U.S. is teaching its children is changing at a rapid pace with more than 2,300 school districts nationwide having tablets involved in the classroom. This combined with year to year local changes in curriculum have seen teachers, like Curran, to see going back to college as a necessity.

“It’s not so much [about] the money [but rather] being better at what I do,” Curran said. “To meet the kids’ needs today you have to go back to school. If you’re going to be a teacher you have to be a lifelong learner.”

National and several state governments have passed programs in order to incentivize teachers in pursuing a higher education. Incentives such as the Teacher Loan Forgiveness program, through the Department of Education, are intended to encourage teachers to fulfill higher education aspirations. On a local level, action and support networks seem to be maintained, at least in some districts. Kirkwood School District (KSD) teachers enjoy the full support of the KSD board.

“We are very supportive and there is a monetary benefit to the staff member as well,” Daniel Frost, president of the KSD board, said.

Working classroom-to-classroom, these teachers, and many more, have experienced emotional, mental and physical hurdles in pursuing their higher education. Ultimately, these teachers trained to be educators, but they see themselves as much more.

“I’ll do anything to reach that one person, and at the end of the day I can reach that one person, I know I’ve done my job,” Lee said.