More than a year ago, the very first player signed by St. Louis City SC was a center back from Ghana by the name of Joshua Yaro. By signing Yaro, City moved the Yaro’s foundation’s (figurative) headquarters to St. Louis. The Yaro Foundation works in rural areas of Ghana to supply school children with the materials that make education possible. Yaro said uniforms are mandatory to attend school in Ghana, so the foundation provides those along with other supplies, like pencils and books.

“Since I was young, I always knew if I ever made it as a professional soccer player, I would want to give back to where I was from,” Yaro said. “[Being from Ghana,] I knew that in the cities, the educational system is great, but once you get out of the cities, it can get pretty bad. I thought of ways I could give back to my country and community, and for me, education is the best possible way.”

Yaro said he grew up in Kumasi, a city in Ghana, but left to attend the Right to Dream School, a boarding school for young soccer players in Old Akrade, Ghana. He then moved to the states and eventually played college soccer at Georgetown University before being drafted by the Philadelphia Union in 2016. Upon signing his first professional contract with the Philadelphia Union, he immediately started his charity.

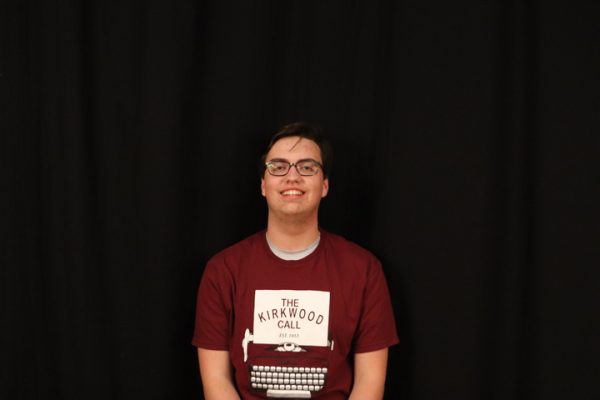

“As a person, he’s kind of always thinking about other people,” Caroline Caciano, graphic design and photography teacher at KHS along with being involved in the Yaro Foundation, said. “[The charity] is kind of a natural way for him to do what he is passionate about.”

Caciano said she drew some blueprints for the Yaro Foundation’s biggest project yet, designing and buildings new classrooms for three different schools in rural Ghana. They will break ground on the construction in January 2024, along with doing construction on another school that has been completely outdoors and another’s whose roof has collapsed..

“It’s not big at all,” Yaro said. “When I started [the foundation], it was me doing most things. I had my agent, who’s also a lawyer, help with the legal side, and I had other people that volunteered their time to help, but it’s not big. I think the work we’ve done over the years has been impactful, though.”

Yaro said he visited all three schools on a trip to help with a school supply drive two years ago. It was one of the only times he’s seen the schools he’s helping.

“You look around and you think ‘This doesn’t seem like anything major,’” Yaro said. “But then you meet with the families and the kids, and just hearing from them how much of a difference it made in their lives was pretty rewarding.”

Yaro said many of the educational problems in rural Ghana are the result of the Ghanaian government’s focus on schools in the city. Both of Yaro’s parents were teachers and would talk about their frustration with the government.

“Most of everything I’m doing through the foundation is the government’s responsibility,” Yaro said. “I want to get to the point where I’m consistently building infrastructure for schools. Imagine coming to school and not having an actual classroom. That’s tough. Not having a place to sit and study makes it hard to enjoy school.”

In the world of sports, education can often be seen as a hindrance to sporting development. Many see the lessons learned in school as inapplicable to their sport. Yaro takes the opposite view, which has been fostered by his parents, who were both educators in Ghana.

“When I was in Ghana, my goal was to turn 18 and sign my first professional contract right away,” Yaro said. “But my mom was like ‘No. You’re not going to do that,’ because she knew the importance of education. The career of professional athletes is really short. So when you’re done, what are you gonna do with your life? I feel like everything I’ve achieved in my professional life has been through education. And that belief in the importance of education was instilled in me by my parents.”

Caciano said that Yaros’ parents did more than just instill an importance for education. They also taught him to give back.

“He knows the value of giving back to other people and that’s something that I know that his parents really instilled in him,” Caciano said. “They gave so much to other people around them and his mom always told him, ‘I’m not doing this for myself, or to feel good about myself. I’m doing it because in life, [these] things come back to you.’ Growing up [and] seeing his parents be so generous and charitable, he then really understood why it’s important to give back to other people instead of hoarding everything for yourself.”