Your donation will support the student journalists of Kirkwood High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Sweet victory: The story of Jay Leeuwenburg

October 20, 2020

There’s a word people use to describe football players who eat candy or drink soda during games: retired. That wasn’t Jay Leeuwenburg.

Before the nine NFL seasons, the unanimous All-American selection and even the inaugural snaps of his organized football career, Leeuwenburg, 1987 KHS graduate, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. At 12 years old, most kids fixate on the future, not the present; Leeuwenburg was determined to ensure that his diabetes would not dictate his reality.

Relentless, unwavering dedication eventually became Leeuwenburg’s predominant trait — and it shone brightly when a mild injury devolved into one much more serious.

“Jay had stepped on a piece of glass in the parking lot and cut his foot,” Dale Collier, former KHS head varsity football coach, said. “We patched it up and he went home, [but then] all of a sudden his dad is telling me they’re going to amputate his foot. It’s like, ‘What are you talking about?’ You go to the hospital and see this young man laying there, [and you gain] this unbelievable sense that [he’s] got to get through this.”

And he did — eventually. An infection hijacked the gash’s initial healing process and began to consume one of the bones in his foot, although an amputation never occurred. Two weeks into his hospitalization, Leeuwenburg was presented with another impediment: school.

“I was failing out of AP Calculus and English at the time, [so] I would have to go into school specifically for those two classes to make sure that I could graduate,” Leeuwenburg said. “They would administer the medication intravenously before I went to school. [After school], I’d come back and get a second dose of it — and I did that for four weeks.”

Six weeks after the shard of glass nearly ended his football journey, Leeuwenburg resumed practicing and eventually reintegrated himself back onto the field. College interest in the offensive lineman — including attention from Notre Dame, who at the time was the nation’s premier football team — had cooled following his return, with programs now tepid to recruit a player whose re-injury risk was unknown. Had the Pioneers missed the 1986 state playoffs, Leeuwenburg might have received no offers at all.

“In our state semi-final game, we played Hazelwood Central, and they had a defensive tackle, [Mario Johnson], who also played fullback for them,” Leeuwenburg said. “He was only a junior, and I was a senior, but the University of Colorado was out recruiting him, and I had a great playoff game against him. That’s what got me recruited to Colorado.”

Colorado may not have even known how dominant of a player they were recruiting — but St. Louis area high schools certainly did.

“A friend of mine, [a high school football coach], said, ‘We had to gameplan more for Jay Leeuwenburg than for Alvin Miller,’ and I said, ‘What are you talking about?’” Dr. David Holley, former KHS principal and head varsity basketball coach, said. “[My friend] said, ‘Jay Leeuwenburg was so dominant [that] our whole gameplan when we played Kirkwood those two years, when he was a star, was to gameplan so that we would stay away from Jay.’”

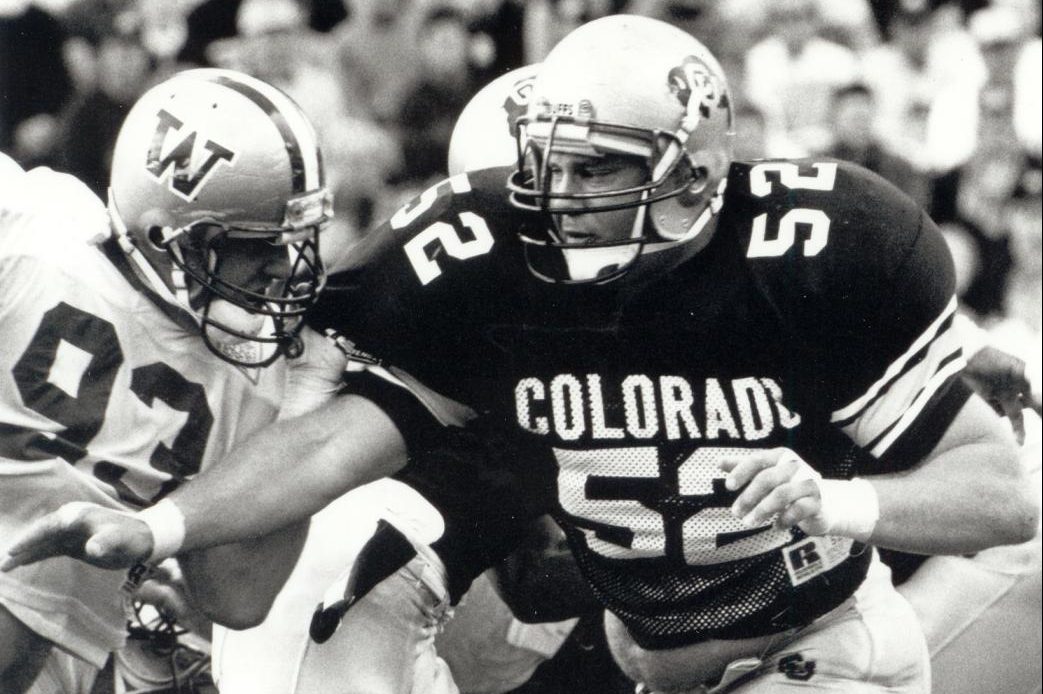

Photo courtesy of the University of Colorado.

College

Translating this dominance to the realm of college football took time. After redshirting his freshman year (i.e., forgoing his first year to develop his skills while maintaining the year of eligibility) and not playing much the following year, Leeuwenburg won a starting slot in the offensive line for the 1989 campaign. Despite averaging a blistering 371.8 rushing yards per game that season and winning each of their first eleven games, the Buffaloes lost to Notre Dame in the Orange Bowl, ending their bid for an undefeated season. Yet even with the loss, Colorado had cemented itself among the nation’s top teams, glowing with leadership at each position — including from Leeuwenburg.

“Jay made the line calls, so he got the entire offensive line in sequence,” Michael Simmons, 1986 KHS graduate and teammate of Leeuwenburg at Colorado, said. “That’s where I go back to Jay being a very smart football player, since it all starts up front. We wouldn’t [have been] able to rush for 300 yards per game if the line wasn’t in sync, and that offensive line was led by Jay Leeuwenburg.”

That offensive line was inspired by him, too.

“It’s pretty incredible and remarkable [to me] that, having been brought up the way he was with diabetes, he was able to be the incredible athlete that he was and control it,” Joe Garten, former NFL offensive lineman and teammate of Leeuwenburg at Colorado, said. “The guy is a hard-worker. He wasn’t the strongest person. He wasn’t the strongest player. He wasn’t the fastest — but he had the drive to be great.”

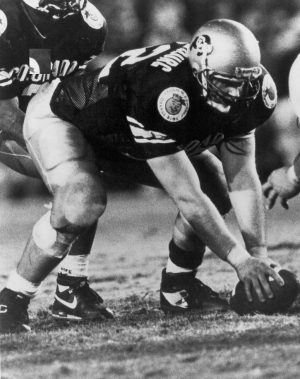

This work ethic, as well as the Buffaloes’ inspired championship aspirations following their 1989 Orange Bowl loss, enabled the team’s manifestation of greatness. Despite starting the season 1-1-1 (including a win in the infamous “fifth down game” against the University of Missouri), the Buffaloes made it back to the Orange Bowl — and to another meeting with Notre Dame. After sixty minutes of hard-nosed football, the score was 10-9. There was a new national champion.

The following year, 1991, was Leeuwenburg’s final college season, at the end of which he received consensus All-America honors. He was a prime candidate to be picked in the early rounds of the NFL Draft; he was a national champion, an All-American offensive lineman and he had helmed a Colorado offensive line lauded as one of the best in the country throughout his tenure. On draft day, though, he waited. And waited. And waited.

“I was the ninth center drafted,” Leeuwenburg said. “I was drafted so late in the draft, [the ninth round], that the round doesn’t even exist anymore. I was really upset by that. [It] definitely gave me a chip on my shoulder and motivated me, and I think that had a lot to do with why I went into training camp hungry and ready to prove everybody wrong.”

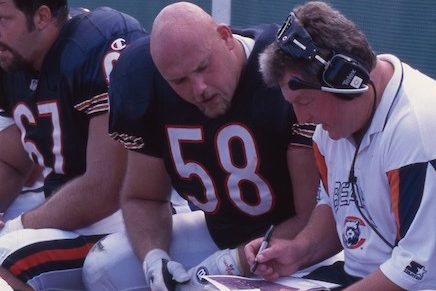

Photo courtesy of the Chicago Bears.

NFL

Before he could prove scouts wrong, Leeuwenburg first had to acclimate to NFL-level football. In the first game of their 1992 NFL preseason, the Kansas City Chiefs, who drafted Leeuwenburg, played against the Green Bay Packers at Lambeau Field. As Garten, who was starting at guard for the Packers, describes, making such adjustments can be difficult for rookie players.

“I just remember [that on] his first series, Jay gave up a sack,” Garten said. “He just kept fighting. It’s pretty difficult as a rookie [because] you don’t play well, [but] he just kept scrapping and had a decent game.”

The Chiefs eventually cut Leeuwenburg, who was then signed by the Chicago Bears. While he did not start any of the twelve games he played in during that 1992 season, he started all 50 games over the next three seasons (including two in the playoffs) — never once missing a snap because of a diabetes-related complication. He didn’t want to detract from the team’s focus.

“I remember vividly while playing with the Bears that I went the wrong way on a play, and we came back to the huddle, I was playing guard at the time, and the right tackle looked at me and went, ‘Dude, is your sugar okay?’ because I had never made a mistake,” Leeuwenburg said. “I wanted to know that my teammates could depend on me on the line or during the huddle that, if I made a call, it was the right call. I didn’t want them to ever have to think about whether I was physically, with my diabetes, [capable] because that to me would be a distraction.”

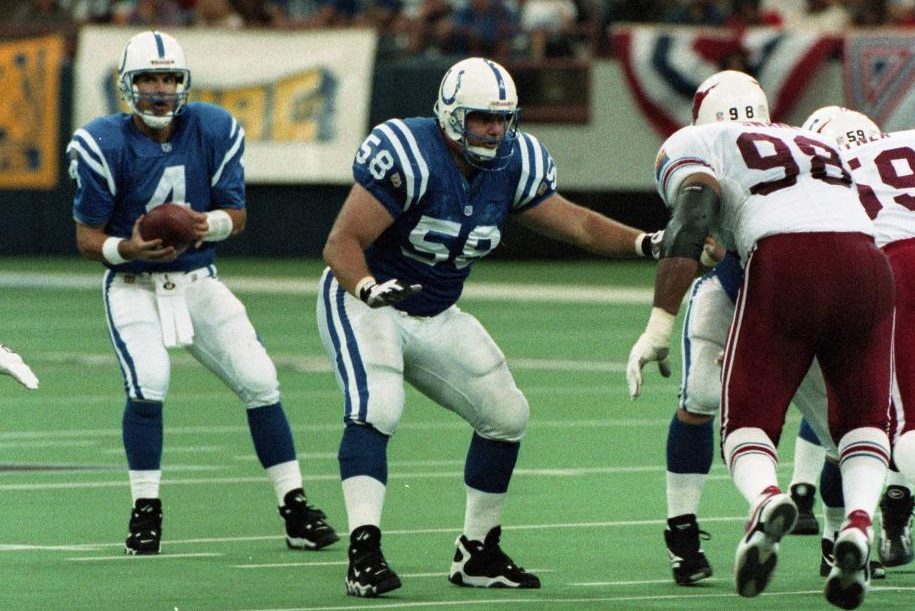

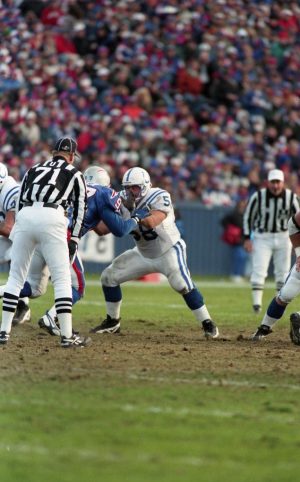

Over the following five seasons, Leeuwenburg floated between franchises in different divisions and conferences: the Indianapolis Colts of the AFC South, the Cincinnati Bengals of the AFC North and the Washington Football Team of the NFC East.

He never made a Pro Bowl. He never won an NFL championship. Each season, each series and each snap reflected the spirited determination with which Leeuwenburg hoped to confront each challenge, especially when playing Hall-of-Fame opponents.

“[My] offensive line coach [on the Bears] called me up a week before our opener against the Giants and said he had some good news and some bad news,” Leeuwenburg said. “He said the good news was that I was starting, and then he goes, ‘But you’re not going to be playing right guard — you’re going to be starting at left tackle against Lawrence Taylor.’ I played against John Randle, Reggie White, Warren Sapp [and] Ray Lewis — all amazing players and athletes. I did pretty damn well [against them], [and] when I reflect on it those are the times when I realize how much fun it was. While playing, you don’t have the time to think about [who you’re playing against], and I just had to be super focused to be in the best position to help the team do the best it could do.”

Leeuwenburg now works as an elementary school teacher in Colorado, while also serving as the offensive line coach for a local high school. Transitioning from playing to coaching was initially challenging for him, he says, as it took time to realize he needs to mold the kids into good high school players, not elite NFL prospects. To him, football’s value as a sport transcends accolades, fame and wins.

It’s about making people better people.

“Dale [Collier] taught us [about] being a team, being accountable, having a good time, being competitive [and being] willing to put yourself out on the line,” Leeuwenburg said. “Treating [players] like young men and letting them fail at times when appropriate — to me, that’s being a coach. It’s about helping you become a better human being — not a better football player.”