Redlining’s long lasting mark

Kamina Love and her mother Betty practice urban farming to provide fresh food for themselves and their neighbors. They help provide the kids in the neighborhood with clothes for the winter. Love has also stood up against developers who try to buy out her neighbors. Love said they have seen the effects of an area that fell victim to redlining.

“We only have one legitimate grocery store, they don’t give us enough healthy food to eat,” Love said. “Now we have a neighborhood market that is black-owned and operated. We have jobs here, but we are very limited once again because of the opportunity and the platform that is placed here. We would have to go outside of East St. Louis to find jobs.”

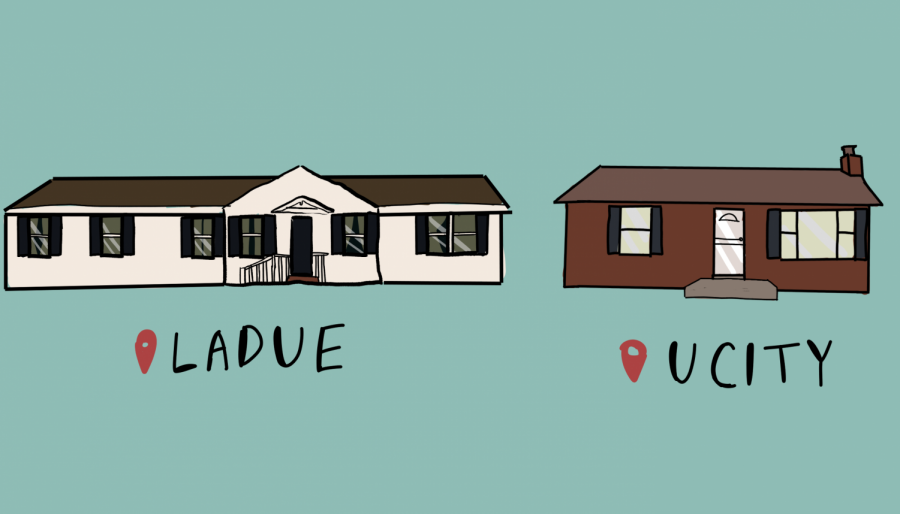

In his report, “The Making of Ferguson,” Richard Rothstein, historian and author of “The Color of Law,” said that events reflecting this racial tension, such as the shooting of Michael Brown, are largely a result of years of housing policies such as zoning and redlining, the refusal of mortgages and insurance based on race, and its effects on those areas. Dr. Jason Purnell, associate professor at Washington University, said these problems in residential segregation have been an issue in St. Louis for quite a while, and have been shown through old state and federal acts that still have a role in the opportunity given to certain areas.

“[St. Louis] had a longer period for racism to [develop], and it was aided and abetted by the government, and local agencies like banks and insurance companies that helped to perpetuate it,” Purnell said. “[The percentage of poverty] creates a vicious cycle of disinvestment and disability for people to access [opportunities.]”

According to a 2014 study by For the Sake of All, a report on the health of African Americans in St.Louis, there was a 18-year difference in life expectancy depending on which side of the city you lived in St.Louis. Purnell said this isn’t due to the individual’s efforts, but the situation of life they’ve been put in.

“Particularly in the last 40 years of our political development, there is a sense that people are on their own,” Purnell said. “We have to remediate and reverse over a hundred years of housing policy that has failed to give opportunity equally to people all over the United States including in St. Louis.”

Love feels that the community is not having a say in its development, and it is not for the benefit of the current residents but for the developers who want the land. According to Love the decrease in the value of the homes as a result of redlining policies has allowed developers to pay significantly low prices to buy out people’s homes.

“We need to be at the table,” Love said. “If they don’t want to bring us a seat we need to bring a seat. I don’t have that much income to move out of East St. Louis, but you only offer me $800 to move out of my house and relocate. People’s grandmothers are being kicked out. Once again we are being robbed.”

According to Joe Edwards, owner of Blueberry Hill and The Peacock Diner in the Loop, the area has been able to escape the effects of the housing policies that divided the neighborhood through white flight, where real estate agents scare white families out of the neighborhood through talk of African Americans moving in. Edwards said they escaped being divided through investment in diversity.

“It was at that time that a bunch of people in our area dug in their heels and said ‘this is crazy, let’s embrace diversity and let’s make that a strength in our area,’” Edwards said. “A lot of open-minded and tolerant people stayed and moved in, and worked together to revitalize the area.”

The development of the area has included the building of new shops along The Loop. A development that Edwards said has provided jobs for the surrounding communities, and created a dense network of resources for transportation and opportunities.

When Edwards first came to the neighborhood his goal was to open a place where he could play his records with Blueberry Hill. However, it was through the opening that Edwards became aware of the need for development in the area.

“Within a week of opening Blueberry Hill I realized that if I didn’t work on the area Blueberry Hill wouldn’t make it,” Edwards said. “So I got people together and over a long period of time it has started to work. The more people that are around each other, the more comfortable they will feel and the better they will feel about themselves.”