Your donation will support the student journalists of Kirkwood High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

NFL

September 30, 2020

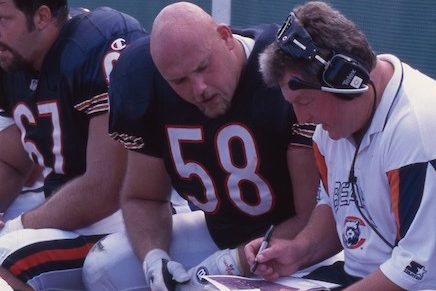

Photo courtesy of the Chicago Bears.

Before he could prove scouts wrong, Leeuwenburg first had to acclimate to NFL-level football. In the first game of their 1992 NFL preseason, the Kansas City Chiefs, who drafted Leeuwenburg, played against the Green Bay Packers at Lambeau Field. As Garten, who was starting at guard for the Packers, describes, making such adjustments can be difficult for rookie players.

“I just remember [that on] his first series, Jay gave up a sack,” Garten said. “He just kept fighting. It’s pretty difficult as a rookie [because] you don’t play well, [but] he just kept scrapping and had a decent game.”

The Chiefs eventually cut Leeuwenburg, who was then signed by the Chicago Bears. While he did not start any of the twelve games he played in during that 1992 season, he started all 50 games over the next three seasons (including two in the playoffs) — never once missing a snap because of a diabetes-related complication. He didn’t want to detract from the team’s focus.

“I remember vividly while playing with the Bears that I went the wrong way on a play, and we came back to the huddle, I was playing guard at the time, and the right tackle looked at me and went, ‘Dude, is your sugar okay?’ because I had never made a mistake,” Leeuwenburg said. “I wanted to know that my teammates could depend on me on the line or during the huddle that, if I made a call, it was the right call. I didn’t want them to ever have to think about whether I was physically, with my diabetes, [capable] because that to me would be a distraction.”

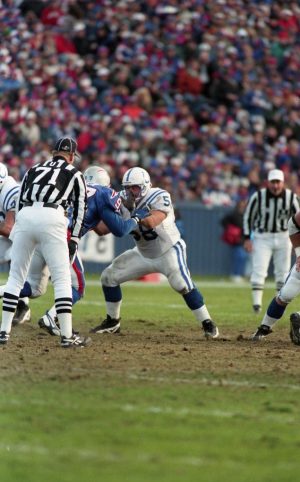

Over the following five seasons, Leeuwenburg floated between franchises in different divisions and conferences: the Indianapolis Colts of the AFC South, the Cincinnati Bengals of the AFC North and the Washington Football Team of the NFC East.

He never made a Pro Bowl. He never won an NFL championship. Each season, each series and each snap reflected the spirited determination with which Leeuwenburg hoped to confront each challenge, especially when playing Hall-of-Fame opponents.

“[My] offensive line coach [on the Bears] called me up a week before our opener against the Giants and said he had some good news and some bad news,” Leeuwenburg said. “He said the good news was that I was starting, and then he goes, ‘But you’re not going to be playing right guard — you’re going to be starting at left tackle against Lawrence Taylor.’ I played against John Randle, Reggie White, Warren Sapp [and] Ray Lewis — all amazing players and athletes. I did pretty damn well [against them], [and] when I reflect on it those are the times when I realize how much fun it was. While playing, you don’t have the time to think about [who you’re playing against], and I just had to be super focused to be in the best position to help the team do the best it could do.”

Leeuwenburg now works as an elementary school teacher in Colorado, while also serving as the offensive line coach for a local high school. Transitioning from playing to coaching was initially challenging for him, he says, as it took time to realize he needs to mold the kids into good high school players, not elite NFL prospects. To him, football’s value as a sport transcends accolades, fame and wins.

It’s about making people better people.

“Dale [Collier] taught us [about] being a team, being accountable, having a good time, being competitive [and being] willing to put yourself out on the line,” Leeuwenburg said. “Treating [players] like young men and letting them fail at times when appropriate — to me, that’s being a coach. It’s about helping you become a better human being — not a better football player.”