Safety in numbers

In 1973, the Meacham Park neighborhood was divided into three elementary school sections to help further integration of Black students into Kirkwood schools. Almost 50 years later, these boundaries still create a divide in the Meacham Park community.

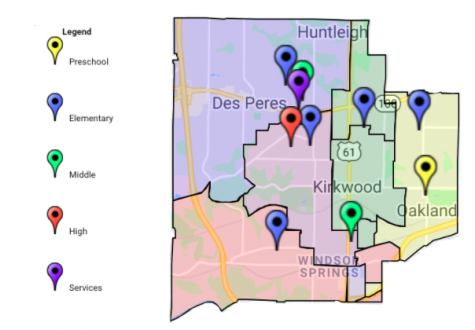

It’s 3:30 p.m. Across Kirkwood, KSD elementary schoolers go home, have their afternoon snack and run outside to play with their neighbors. The kids who live on Electric St. in Meacham Park ride the bus home from Robinson and wait for their friends across the street to get home from North Glendale. Unlike other neighborhoods within KSD, Meacham Park students are split up between three different elementary schools, even if they’re not attending the school closest to them.

Bum Yong Kim, KSD parent, is a member of the Meacham Park Neighborhood Improvement Association (MNIA). MNIA has voiced its concerns to KSD about the way Meacham Park is divided and the negative effects this has on the kids’ social and emotional development.

“The idea that some of the kids would be going to different elementary schools is really detrimental in having space to build friendships within the neighborhood,” Kim said. “By splitting up the kids, you’re creating a barrier, and you’re asking the kids here in Meacham Park to pay a higher price than you are other children who are allowed to attend the same school as their neighbors.”

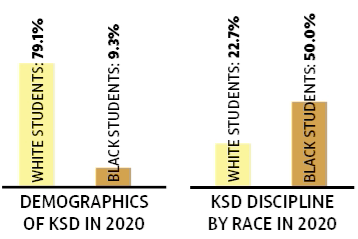

Kim and other parents want to know why the district splits up Meacham Park students more than other neighborhoods. Kim said it feels to them as if the district is using minorities and dividing Meacham Park in order to diversify the elementary schools. KSD Assistant Superintendent for Data, Intervention and Supports Matt Bailey said the boundary lines were drawn to further integrate schools after KSD began the desegregation process in 1954. The boundaries have not been changed since they were drawn in 1973.

“Because of the way our students were distributed across the district, there was a need for us to redraw the lines to ensure a little bit more racial balance amongst all the schools,” Bailey said. “Most of our African-American students that live in the district live in that area, and so they were divided up to go to three different elementary schools – Westchester, North Glendale and Robinson. That’s why those boundaries are drawn the way they are in Meacham Park – because the schools were not as integrated as they could be.”

Prior to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision which forced districts to integrate schools, Black students in Kirkwood attended one of two elementary schools: Booker T. Washington School, which closed in 1950, or J. Milton Turner School. Wallace Ward, former KSD school board president and current Kirkwood City Council member, had a sister who attended segregated schools in Kirkwood. He attended elementary school after integration. Ward said the district’s boundary issues stem from years of overcrowding and efforts to achieve racial balance in schools in the early 1970s.

“If you look at the social network that [was] found around our schools, that was the concept of [a] neighborhood school – your family was clustered around schools where everybody went to school and the families knew each other and parents knew each other,” Ward said. “Well, those families [in Meacham Park] lost that connectivity. And we continue to do that today.”

Proposition R, a zero-tax rate increase bond proposed by KSD, will be on the ballot April 6. The proposition includes expanding some elementary schools and redrawing current school boundary lines to account for overcrowding. This provides the district with the opportunity to change the way they divide Meacham Park. However, this is easier said than done and might not even appeal to every Meacham Park resident, according to Ward.

“It’s a hard thing,” Ward said. “There’s not an easy fix because those families who are in Meacham Park, some of them are just as attached to going to North Glendale and would hate the idea of moving from there. So it’s a very complex problem and I think the district’s [going to] have its hands full trying to compromise to meet those issues that those families have. Anybody who served on a school board will tell you that one of the hardest things you can do is [draw] new attendance boundaries. It is always fraught with a lot of emotional peril.”

Shaquari Jackson, junior, lives in Meacham Park and attended Robinson Elementary. She said readjusting the boundary lines would help Meacham Park students academically by allowing them to help one another with homework. However, thanks to the tight-knit community in Meacham Park, she doesn’t think it will make much of a change socially.

“I always thought [going to different schools] was weird, but it didn’t really matter to me, because we have a park,” Jackson said. “After school, everybody would just always go to the park, so we still knew each other. We all got out at the same time and we’d all see each other get off the bus. We knew each other because we lived in the same neighborhood.”

Along with the emotional aspect, redrawing school boundary lines is a complex, multi-year process that hasn’t been done since the original Meacham Park boundaries were put in place in 1973, according to Bailey. The process begins with KSD’s boundary adjustment team gathering input from community members. After discussion and feedback, the final plans will require approval from the KSD Board of Education. Bailey said the main goal of redrawing boundaries is to fix overcrowding in Kirkwood schools, but that the current Meacham Park division may or may not change in the process, depending on the wants and needs of community members.

“When you’re running something like Prop R, you take as much input from as many groups as you can,” Bailey said. “We haven’t done this for 40-plus years in Kirkwood. Generations of people have gone through our school systems without these boundaries changing. We want to make sure we take our time, that we get a lot of community feedback and that we provide our families with some opportunities to have a phased in approach.”

Bailey stressed the importance of community involvement in the decision making process, saying it is one of the district’s main priorities. He also said families will have the option to stay at their old school instead of immediately switching with the new boundaries, giving them more flexibility and time to adjust. KSD representatives have met with MNIA as well as many individual Meacham Park residents to hear the ideas on the possible adjustment of school boundaries.

“We want to make sure we’re talking to the folks that are most impacted by those boundaries,” Bailey said. “We really have done a lot of that work laying that foundational work and some of that work has informed the decisions and the opportunities that we have for Prop R to look at what the right solution is gonna be for our community.”

Despite the long, complicated process adjusting school boundaries entails, Kim said it is worth it to have children, especially those in minority groups, go to school with other kids like them. He compared the situation to the way native English speakers prefer to attend English-speaking schools in foreign countries.

“[Students] are more comfortable having other people who look like them, sound like them, have the same cultural expectations and backgrounds – that creates a safer environment for them,” Kim said. “When you split them up, you’re actually diffusing the social safety net that they have. During desegregation, only a handful of Black students went to white schools and they were totally harassed. Imagine if it wasn’t just a handful that went to that school, but more like at least 30 or 40 that went to integrate schools. That doesn’t guarantee that racism isn’t [going to] happen, but I will guarantee that they feel much more solidarity and safety when they aren’t the only Black person in class, the only Asian person in class, the only Hispanic person. And so by splitting up all of the minority children to diversify all of these other schools, you’re diffusing that safety in numbers.”